The Rise And Fall Of F1's High Wings

They came and went quickly, thanks to Chaparral's inspiration, lots of innovation, and a pair of Team Lotus crashes.

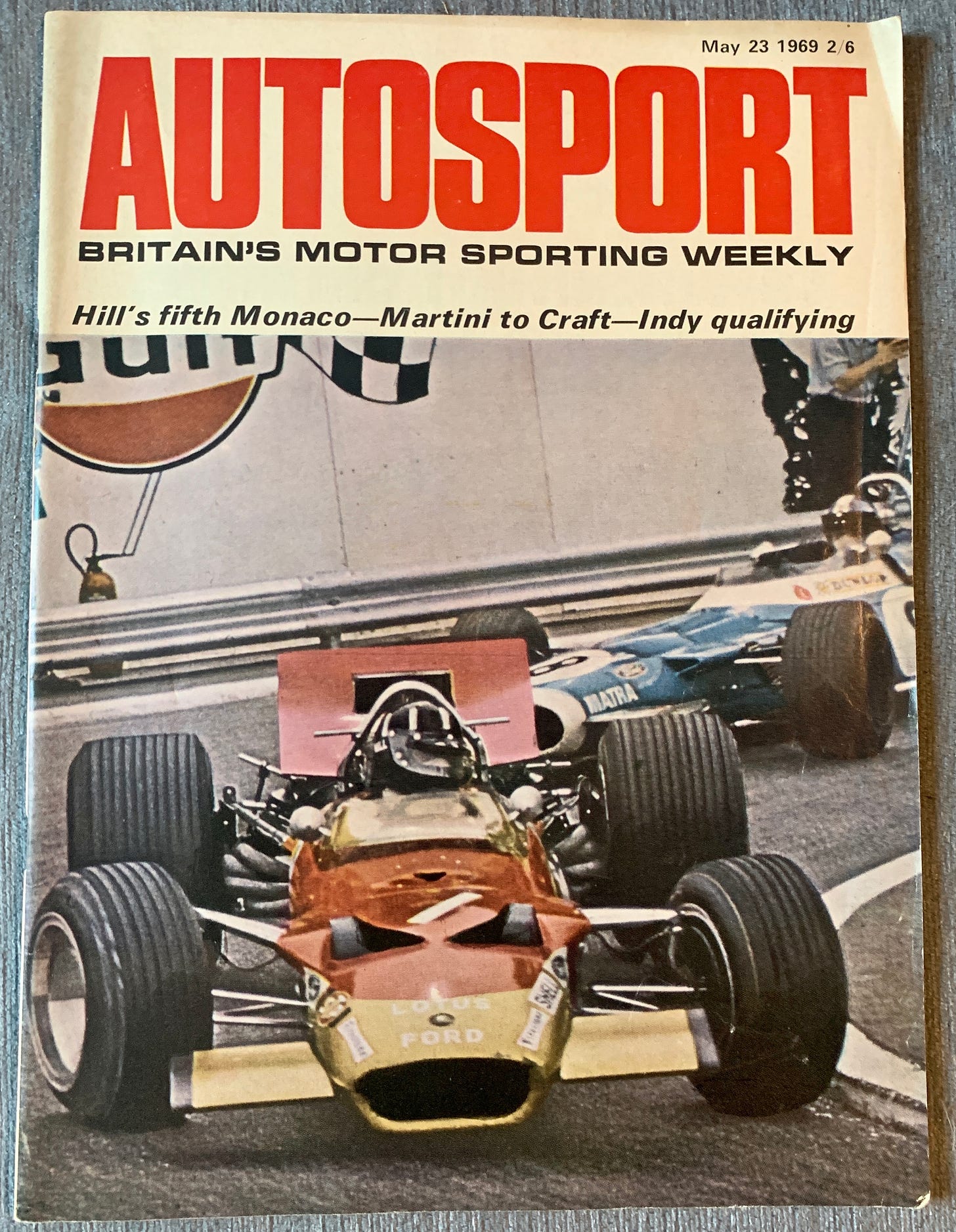

By the time Jochen Rindt's letter appeared in the pages of Autosport magazine's May 23, 1969, issue, the high wings he wanted outlawed from Formula One were no longer allowed.

He'd missed the first race post-ban, at Monaco on May 18, while recovering from a violent wreck during the Spanish Grand Prix held two weeks prior. The crash's cause: a loss of control due to a wing failure.

"I was happily driving round the fastest bend on the track when my wing broke and changed its downthrust into reverse," he wrote. "The back end of my car started flying, and I nearly nearly flew over the double guardrail. Fortunately I was...about 10 inches too low and got bounced back into the track."

Considering the number of spectators just beyond the guardrail, it's easy to understand why Rindt welcomed slamming into the fence.

Given the wings' haphazard evolution, it's amazing they lasted as long as they did.

Motorsport wings are the opposite of airplane wings. Racing wings are shaped to provide downforce, which improves a car's grip, helping it go faster around corners. In aviation, of course, wings help lift aircraft off the ground.

Today, wings are a key part of every Formula One (F1) car's design. But the world's most renowned motorsport series was late to the downforce party.

Swiss driver and engineer Michael May is credited with entering the first wing-equipped car in a major race, at the 1956 1000km of Nürburgring. His Porsche 550 Spyder had a well-secured but adjustable airfoil mounted mid-body, directly above the open-topped car's middle.

Complaints from competitors led race organizers to ban the unique addition, however, forcing May to run wingless. Officials claimed the main issue was danger posed by competitors not being able to see around the wing. But the protests were lodged only after May posted some impressive practice and qualifying times, out-running a Porsche factory team, among other notables.

Around this time, U.S. sprint car teams, led by Jim Cushman, were toying with wings.

F1’s introduction to wings would come several years later. Jim Hall, a Texas-based driver, team owner, and constructor, introduced a rear wing on his iconic Chaparral sports car design in 1966. A year later, Hall entered an updated version of the car in the manufacturers' championship series, which featured high-profile events like the 24 Hours of Daytona, 12 Hours of Sebring, and 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Hall's winged wonder won just once--at the season-ending Brands Hatch, England event--but was consistently fast. The race car wing was here to stay and the standard F1 car's profile was about to change forever.

The F1 cars rolled out for the 1968 season looked largely the same as they had for a decade or so: long and thin, like cigars or kazoos with wheels. But things quickly changed.

In the third race of the year, at Monaco on May 26 , Graham Hill's Lotus 49B showed up with small winglets at the front. Hill won the pole and the race.

That seemingly was enough to sprout F1's "aerofoil" era. When the "circus" rolled into Spa for the Belgian Grand Prix two weeks later, various types of wings "could be seen sprouting in all directions," Motor Sport’s Dennis Jenkinson wrote in his race recap.

The teams' innovation was one step ahead of the rule book. Absent regulation on wing size or configuration, teams got creative, trying different wing sizes and affixing them in different spots on the car.

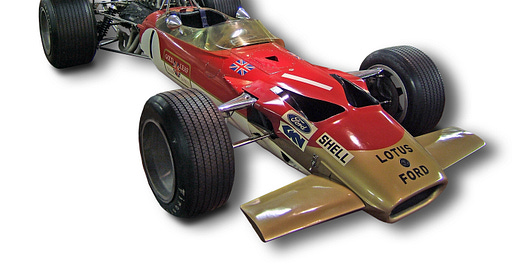

Lotus came up with the configuration that would win out—and ultimately lead to the ban. For the July 7 French Grand Prix, Lotus outfitted its two 49Bs with tall wings attached not to the chassis or engine area, but directly to the rear suspension. The downward force on the tires proved effective, but thin rods used to mount the wings make the configuration look more like an antenna than a cutting-edge motor racing aid.

Lotus driver Jackie Oliver crashed his 49B in practice and the team could not repair the car in time for the race. While race reports don't blame the high wing, some--including Rindt--pointed to the accident as the first clear warning sign that the new designs were unsafe.

Budding Belgian superstar Jacky Ickx won the race. Not only was it his first of eight F1 victories, but it came in a Ferrari 312B with a wing mounted high above its motor, making 1968 French Grand Prix the first F1 race won by an wing-equipped car.

Ickx's victory surely had as much to do with his abilities--though he never won a F1 title, he's consider among motorsport's greatest all-around drivers--as his car's configuration. But that didn't stop the wing trend's expansion.

Subsequent events saw a steady stream of more ambitious configurations for teams that opted for wings. (Some teams resisted, because while wings improve cornering speeds, they slow cars down on high-speed sections. That explains today's F1 DRS--short for Drag Reduction System--that lets drivers open part of the wing and remove some of that drag penalty to improve overtaking.)

The experimentation continued throughout the rest of the 1968 campaign and, following no major offseason wing-regulation changes, into 1969. Among the new configurations were dual high-wing designs featuring airfoils attached to both the front and rear suspensions.

The season-opening South African Grand Prix at Kyalami on March 1 showed the wings were working. Both the winning Matra of Jackie Stewart and runner-up Graham Hill's Lotus were dual high-wing designs. Rindt, also in a dual-wing Lotus, was second-fastest qualifier, but dropped out of the race with a mechanical issue.

Teams kept tinkering with their designs. At the next race four weeks later, the Spanish Grand Prix at Barcelona's Montjuïc circuit, Lotus opted for a single, taller rear wing, and their cars were fast. Rindt grabbed the pole and Hill qualified third.

Their speed carried over into race day. Rindt led the way early while Hill settled into third. As Hill's Lotus crested the hill heading towards Montjuïc's Turn 1 hairpin, he lost control and crashed hard, bouncing between the inside and outside barriers.

"Something had obviously broken, although at the time Hill was not sure what it was," Motor Sport's Andrew Marriott wrote.

Thirteen laps later, Rindt lost control at the same spot. This time, however, the cause was clear: witnesses saw his wing collapse. Out of control at 140mph, Rindt hit the barrier, clipped Hill's wrecked car, and flipped over.

Considering the accident's severity, Rindt was lucky. He suffered fractured skull and broken nose.

He was also done with high wings.

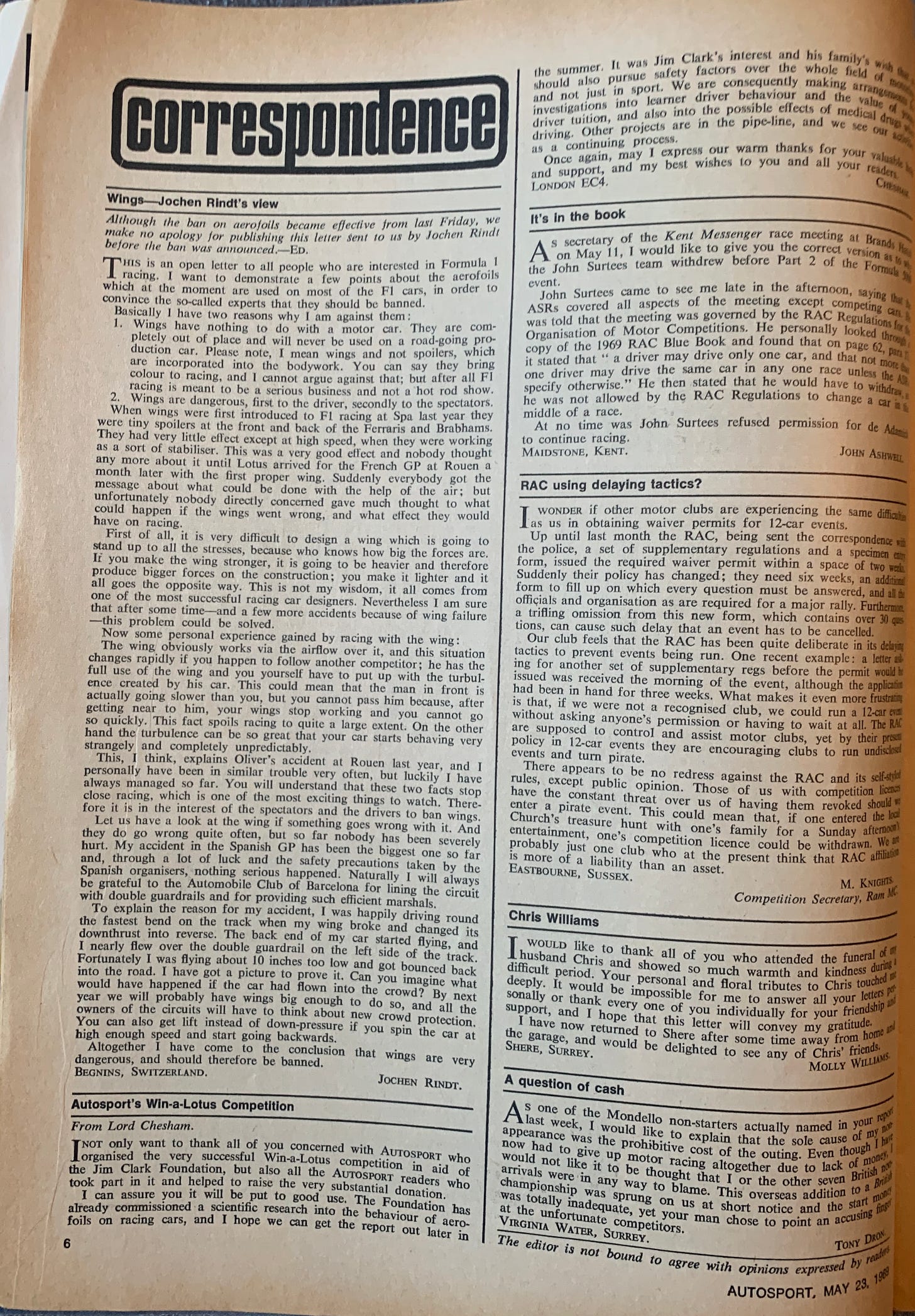

While recovering in Switzerland, Rindt did some writing. In a 778-word open letter, he called for a ban on "aerofoils," citing his own experience and the lack of firm understanding on how they effect race car designs.

Unexpected turbulence is another issue, he added. "This, I think, explains Oliver's accident [in France] last year, and I personally have been in similar trouble very often," Rindt wrote.

Following his Spanish Grand Prix accident--"the biggest one so far" linked to wing failure, he noted--Rindt had seen enough.

"Altogether I have come to the conclusion that wings are very dangerous, and should therefore be banned," he wrote.

The issue was settled at Monaco, but only after significant race-weekend deliberations. Local race organizers lobbied for a voluntary ban. Every team but one, Matra, agreed. Matra’s complaint: the other teams were bolting wings onto older designs, but it developed its car after wings came to be in 1968.

Facing an impasse and lacking the authority to change F1 regulations, Monaco’s organizers permitted wings at the first practice. But behind the scenes, they lobbied members of CSI, F1’s governing body, to consider an emergency ban.

CSI agreed, and immediately outlawed the riskiest wing designs until reasonable, justifiable regulations could be set.

Hill, Rindt's Lotus teammate, won Monaco with help from modest--and legal--front and rear fins.

The May 23, 1969 issue of Autosport magazine went to press the Friday after Monaco--one week after the ban. But Rindt's letter ran anyway.

Wrote Autosport editor Simon Taylor: "We make no apology for publishing this letter sent to us by Jochen Rindt before the ban was announced."

More from On Motorsport

The Howmet TX and the Summer Of '68

Winning races at two long-forgotten tracks on back-to-back weekends is hardly the stuff of a golden era. In the case of the Howmet TX, however, four wins in four outings in June 1968 is as good as it got--and it was pretty good.

Goodyear's Out-sized Effort

Goodyear is no stranger to Le Mans, having provided tires for the LMP2 class for the last several years. But the company brought something new to Circuit de la Sarthe this year--bespoke tires for the race's special Garage 56 entry.

References

Rindt letter--Autosport, May 23, 1969, p 6.

Michael May wing ban--https://www.loveforporsche.com/debut-race-porsche-550a-michael-may-winged-550-1956-nurburgring-1000/

1968 Monaco Grand Prix report--https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/july-1968/43/xxvi-monaco-grand-prix/

F1 sprouts wings at Spa--https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/articles/single-seaters/f1/f1-sprouts-wings/

Jenkinson on 1968 Belgian Grand Prix—https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/database/races/1968-belgian-grand-prix/

1969 Spanish Grand Prix--https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/june-1969/60/spanish-grand-prix-2/

1969 Monaco Grand Prix--Autosport (Patrick McNally), May 23, 1969, pp. 12-19.