Podium Perfection

The No. 38 Performance Tech Motorsports LMP3 team heads to Sebring after grinding its way to a podium finish at IMSA's season-opening Rolex 24. The performance will be a tough act to follow.

Podium finishes never come easy in endurance racing. But some prove to be much more difficult than others.

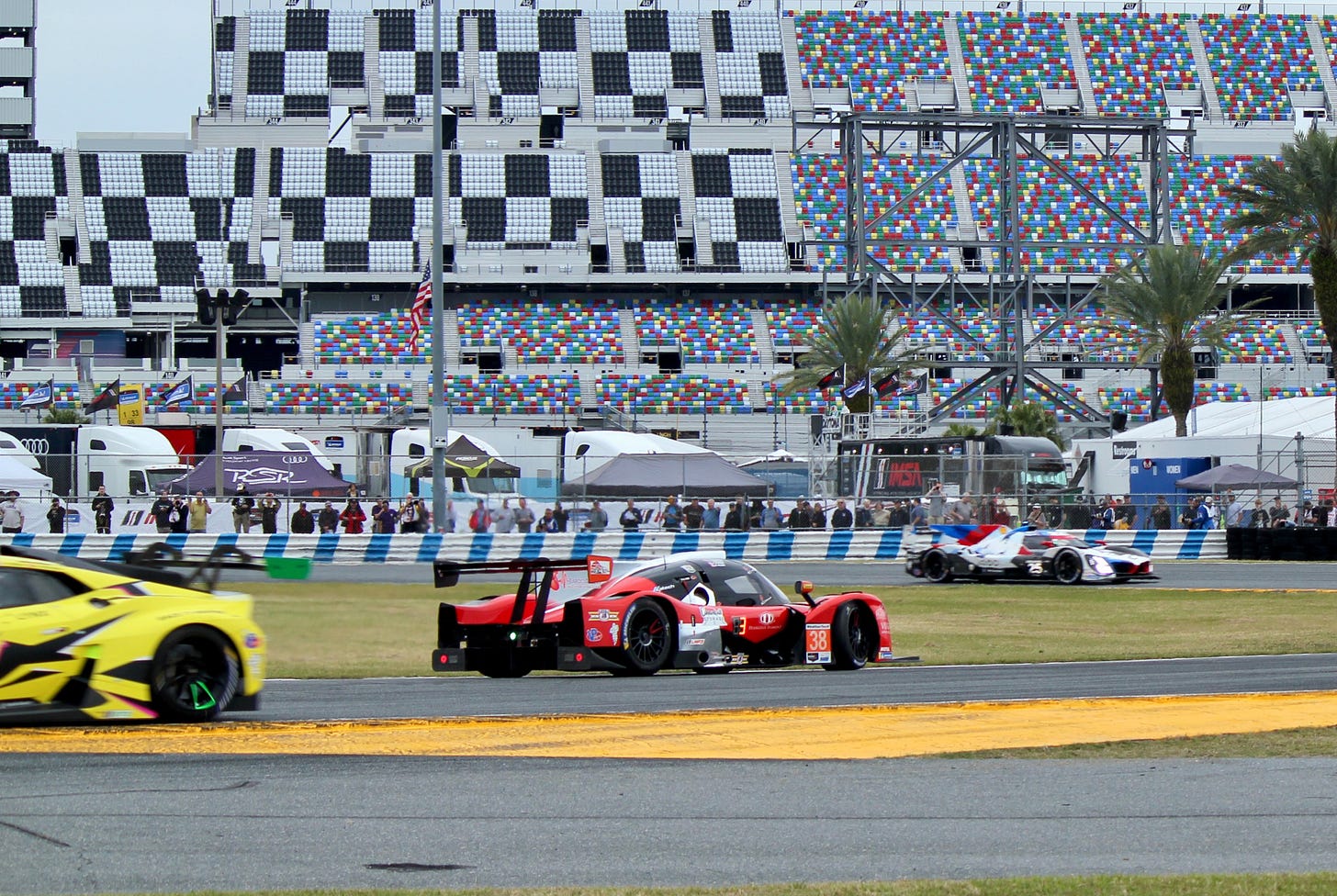

The No. 38 Performance Tech Motorsports (PTM) team will roll off at the 12 Hours of Sebring March 18 looking to top its third-place LMP3-class finish in the IMSA WeatherTech Sportscar Championship season-opening Rolex 24. No matter how the event unfolds, however, it's hard to envision the team authoring a more compelling storyline than its Daytona saga.

PTM rolled into Daytona with a four-driver lineup. But only one, Australian Cameron Shields, had run the Rolex 24 before. The others, Chris Allen, Connor Bloum, and John DeAngelis, had a lot to learn.

Despite the lack of experience, the team had confidence--and a plan.

"Even if we were a second or two off on pace per lap, we thought just as long as we can run a clean race, stay out of trouble, avoid dumb penalties, and do our thing, we could end up on the podium," Allen recalled a few weeks after helping the team do just that. "Our goal, first of all, was to finish. But if we ran a smart race, we genuinely thought we could be in a top-three position with that strategy."

PTM founder and principal Brett O'Neill launched the team in 1982 with the goal of helping drivers climb the racing ladder. The team's trophy case includes multiple full-season IMSA titles in various classes and a handful of major wins and podium finishes, including third at last year's 12 Hours of Sebring.

The driver roster has featured a few familiar names as well. Among them: rising IndyCar star Pato O'Ward, who in 2018 helped PTM to class wins in both the Rolex 24 and 12 Hours of Sebring when he was just 17.

But mostly, and like most IMSA sports-car entries below the top class, PTM leverages gentlemen drivers--aspiring pro racers or unabashed hobbyists--to fill out their rosters. These drivers bring various levels of experience, and always some level of funding.

Allen, the only driver from PTM's 2023 Daytona entry who will drive for the team at Sebring, grew up a car nut and began racing in 2014. After a few years in GT cars and a stint in Europe, he got behind the wheel of a prototype--and was hooked. He ran his first IMSA race last year, driving for PTM at Virginia International Raceway.

An avid classic car collector, he owns Cannonball Storage, a high-end vehicle storage business near Philadelphia. When he drives, Cannonball Storage rides along as a sponsor. He also makes sure the VOGM (Vein of Galen Malformation) Support Network, a nonprofit he supports, gets exposure, too.

Even with three drivers making their Rolex 24 debuts, PTM's track record meant it headed into Daytona with confidence.

"We have proven ourselves to be podium contenders, so we expect to bring home some hardware from Daytona," O'Neill said in the lead-up to race day.

Qualifying showed O'Neill's expectations were realistic. Shields piloted the No. 38 Ligier JS P320 to the third-fastest time out of nine LMP3 entries, posting a lap time of 1:43.351--just 0.154 seconds behind the top qualifier.

Having shown podium-level speed in a 15-minute qualifying session, the team focused on getting the car set up for a 24-hour marathon and getting three Rolex rookies up to speed.

Daytona's 3.56-mile, 13-turn road course is a challenge for even seasoned drivers, combining a series of flat twists and turns with long, flat-out stretches around the historic track's high-banked oval perimeter. Mix in IMSA's multi-class format--this year's Rolex featured five classes of cars, from the top end, purpose-built GTP prototypes to the easily recognizable BMWs, Corvettes, Ferraris, Lamborghinis, and Porsches that packed the two GT classes--and the learning curve for new drivers is steep.

IMSA's race-week prep schedule included four practice sessions for the LMP3 class. The No. 38 car ran into trouble in two of them, forcing unplanned pit stops for work, and in one case, a nose change.

The off-track excursions were nothing major--no walls or other cars were involved. Yet losing even a bit practice time can throw any team off, let alone one with several race rookies. PTM was unmoved.

"In the grand scheme of things, writing a nose off really isn't huge deal," Allen said. "We were back out in that same [practice] session."

Race day brought an early challenge when the No. 38 spun in the infield after making contact with the No. 33 Sean Creech Motorsport LMP3 car during a battle for position in the third hour. A pit-road violation soon followed, and team found itself ninth--dead last--in class, several laps down.

From there, the team stuck to its plan, and the No. 38 slowly worked its way through the LMP3 field. After 20 hours, PTM was second in class, nine laps ahead of its nearest competitor, the No 33 car that sent the No. 38 for its early-race spin.

But trouble was brewing.

The car's clutch was slowly going. At first, the crew worked around it by push-starting the car after each pit stop--a laborious process made even more challenging by IMSA's rules that permit only four crew members over pit wall at a time.

But the problem only worsened. An agonizing 15-minute stay on pit road seemed to signal the end for PTM as the malfunctioning clutch kept the car in gear and unable to start. But an engineer from Katech, a company that provides trackside technical support, saw the problem and offered a fix--pulling a sensor wire would fool the system and force the transmission into neutral.

But now the only way to get the car rolling again was by pushing it. Difficult enough during pit stops, but impossible in the event of an on-track incident, adding another level of pressure for the drivers.

After 21 hours, the No 38 was still second in class, but the gap to third was just two laps.

Halfway through the 22nd hour, Shields brought the No. 38 in for a scheduled pit stop. When it came time to go, the crew pushed the car to the end of pit road to get it started. But Shields couldn’t get the engine fired.

So they pushed it back up pit road and tried again.

No luck.

Finally, after more than eight minutes and three excruciating, manually-powered trips down pit road, the car was back under its own power, and back in the race.

The extended stay on pit road cost PTM second place; the No. 33 Sean Creech ride was now two laps up on the No. 38, which was eight laps up on the fourth-place No. 85 JDC Miller Motorsports entry.

With just 90 minutes to go and a podium in sight, Shields--who jumped back behind the wheel during the three-push pit stop--was tasked with easing the No. 38 home. Two more pit stops went as well as could be expected, with quick push-starts getting the car back on track.

Then, in the final half hour, yet more trouble.

The car was losing brake pressure. The culprit: one of the rear brake rotors had separated from the hat, or part that connects it to the rest of the brake assembly.

With just a two-lap edge on the fourth-place car, an extra pit stop was too risky. So Shields backed off a bit, easing the car through the corners and letting the traffic by.

"The GTD Pro traffic was coming through so we ended up waiving the entire field by," Allen said. "It was definitely bite-my-fingernails time there."

After 721 laps and 2,567 miles, and several anxious moments, Shields brought the No. 38 home in third--and on the podium. The PTM entry finished 16 laps behind the class-winning AWA Racing No. 17 and four laps behind the No. 33.

The gaps suggest that the LMP3 fight wasn't compelling racing. It was the only class that didn't have multiple cars on the lead lap at the end, and one battle--the LMP2 class fight--produced a photo-finish that became instant IMSA legend.

But for PTM, the 2023 Rolex 24 was more than memorable enough.

"That's how endurance racing used to be," Allen said. "Even 10 years ago, it's not like it was a crazy, 24-hour sprint. You really had to preserve the cars and stay off the kerbing. Now these guys are just going balls out for so long. LMP3 in my mind was was more old-school endurance racing. A battle of attrition.

"We were on the podium at the Rolex 24 at Daytona," he added. "It truly doesn’t get much better.”